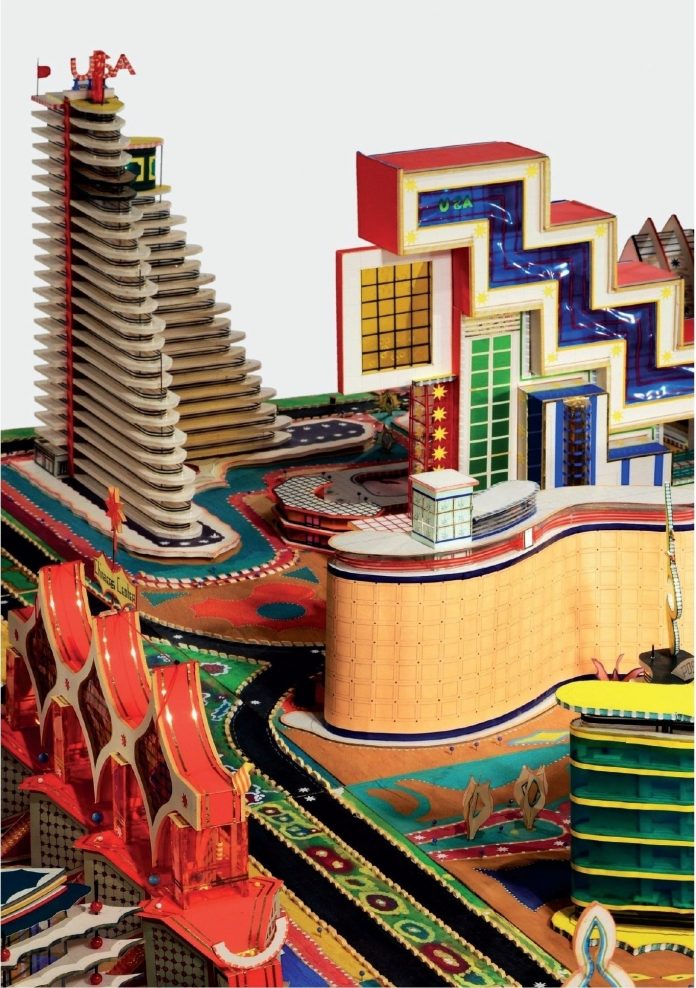

“These depict imaginary buildings and whole cities in a perfectly integral mélange of modern, postmodern, and entirely invented styles, mostly in cut and painted paper, card stock, and plastics, with occasional urban detritus: used packaging, bottle caps, soda cans. The pieces range in height from about a foot to four feet and, in width, from a couple of feet to the nearly nineteen-foot sprawl of the artist’s masterpiece, ‘Ville Fantôme’ (1996), a tableau bristling with skyscrapers engirdled by a ring road.” – Peter Schjeldahl in the 28 May 2018 issue of The New Yorker.

Like many observers of architecture and design, I am generally fascinated by buildings and townscapes. We take upon ourselves the construction of the city – the recreation of the urban and human landscape we inhabit. We idealize an imagined urban intellectual culture. The city itself symbolizes many of the aspects of modernity that we have mandated to ourselves to interpret, mediate, critique, and propagate. In that sense, we see, as Congolese artist Body’s Isak Kingelez did to fantastic effect, that spent packaging is a cheap and malleable material to be deconstructed for making new architectural objects and dream cities.

The work of Kingelez is not only a comment on what packaging is or was – or even that it is simply folded and glued paper and decoration. The same paper and packaging, even once used and discarded, can be used for making structures and cities that inspire future-facing dreams. This is not far from what the original packaging does for the shopper. Or what the supermarket does as it becomes the citadel of dreams for the consumer.

The entire supermarket with its carriages and streets becomes a city and the shelves stacked with packs are the transient or ever-changing walls and buildingscapes that line it. Each package is a brick in the wall, or a house, a piece of the dream that we can carry home to our cosmopolitan refuges of modernity and aspiration. We can bring back something green, red or yellow decorated with the glittering gold and silver that Kingelez loved, just as we do. We can bring back our dreams of Thailand or becoming a superwoman by carrying home a simple box that sustains both body and soul.

Given that we are people watchers and urban anthropologists by nature, and consumption anthropologists by vocation, where does the work of Body’s Isak Kingelez fit into the design of packaging? Kingelez is not the first person to use empty or thrown away packaging for making designs and sculptures – and he is not even the only one in Africa. There is a tradition of artists everywhere, in India, too, of making constructions, designs, maquettes, installations out of paper. In Japan, it is substantial and acknowledged, with several arts such as kirie, origami, and the beautiful sculptures made of spent packaging known as Haruki’s kirigami.

Kingelez was born in 1948 in Kimbembele-Ihunga, a village near Kinshasa, the capital of the Congo that, after independence in 1960, was renamed Zaire. Among other things, he studied industrial design in college in Kinshasa but decided to be a school teacher for two years. After a fever, he started making sculpture out of paper and glue he cut by hand with scissors and a Gillette razor blade – no different than many of our designer and architect friends. He sifted through discarded packaging in his quest for raw material and made sculptural buildings touched up with paint.

A neighbor insisted he show these to the local museum where the staff couldn’t believe that he made the two maquettes he brought. He made another in front of them, and they gave him a job as an art restorer. He worked in the museum for eight years, before devoting all his time to art.

Kingelez was discovered by the west in 1989 and shown for the first time in the Magiciens de la terre exhibition at the Pompidou Centre in Paris. Eventually, his work was shown in 30 countries on six continents. The set designer of the recent academy awardwinning movie Black Panther was inspired by Kingelez’s dream cityscape Ville Fantome made in 1996.

Having been aware of Kingelez for several years, I grabbed my chance to see his work at the Moma exhibition in New York City in the fall of 2018. A Friday when entrance is free to all, the museum was packed, and the exhibition a revelation including a short AI walk-through of the Ville Fantome.

Independence came to the Congo when Kingelez was 12 years old, and although a despot ruled the young country, Kingelez was very motivated by the idea of nation-building and the need to imagine its future. He never had an agent and lived in Kinshasa till the end of his life in 2013. His work reflects many things that include mirroring colonial and cosmopolitan models and the fascination with the skyscraper as an icon of modernity.

The Kingelez maquettes are sometimes bombastic, over the top and don’t make sense much of the time. But he makes us wonder as citizens of a new country – are we urbanists, tourists, or merely shoppers? He gives us an alternate path to the future.